On Shakespeare's Bigotry: An Open Letter

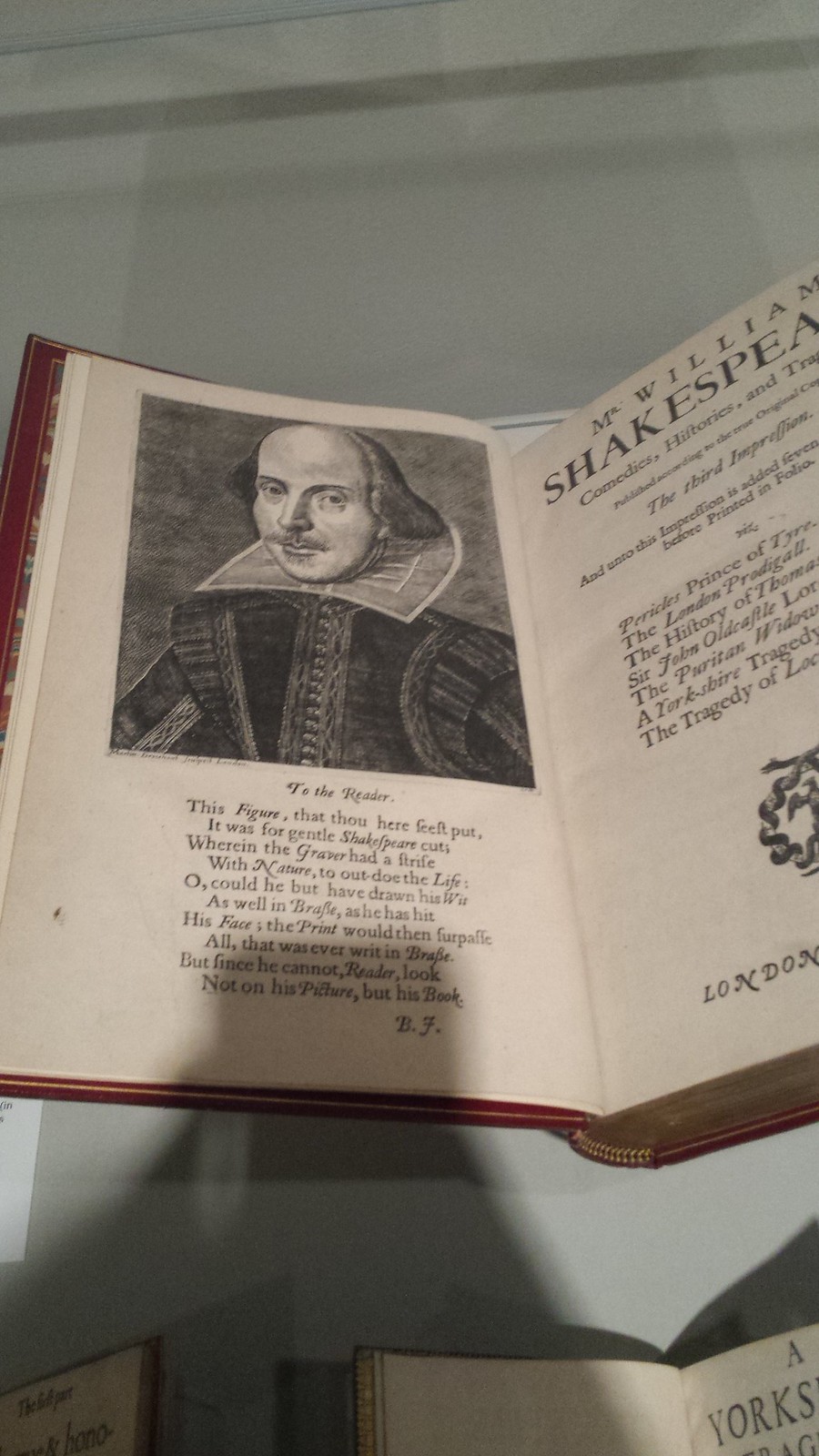

On Tuesday, 13 June 2017, I opened up the Buffalo News to find a perplexing letter to the editor. Someone named Gerhard Falk was calling for an end to the "literary correctness" that kept Shakespeare on our bookshelves and in our syllabi. Gerhard Falk wanted us to "ignore Shakespeare."This was absurd. You cannot, of course, "ignore" a force and a legacy that has shaped our culture, shaped our language, and shaped our understanding of ourselves. On top of that, Falk's charge was a silly, tired one, something high school English teachers address as a prelude to a discussion of historical context and the importance of an author's intentions to the value of a work of literature: namely, that Shakespeare is bigoted, and specifically anti-Semitic.Gerhard Falk, I discovered, is a long-time Buffalo State sociology professor, and a survivor of the Holocaust. The full text of his letter is below:

Recently I read “Hitler” by Joachim Fest. Evidently Adolf Hitler considered “The Merchant of Venice” by William Shakespeare his favorite play because it maligns the Jewish people in the most disgusting manner, thereby undoubtedly contributing to the mass murder of the European Jews.The recent bombings in London and several other such atrocities in England and in the United States demonstrate that there is enough hatred in the world so that we need not teach our children by means of Shakespeare’s bigotry that religious hate is legitimate.After I read “The Merchant of Venice,” I read all of his plays and discovered that his 16th century works are so remote from present day interests that it is unfortunate that “literary correctness” requires us all to pretend that Shakespeare was anything better than an antiquated bore.There is some great literature in this world that is far more supportive of our democratic values than Shakespeare’s hate-mongering. Surely our English teachers know that and would do all of us a favor if they had the courage to ignore Shakespeare in favor of all the great American literature that our children evidently never see.

Gerhard understands the power of bigotry in a way that I never will. Still, he was wrong about Shakespeare, and wrong about the value of literature generally. I had to turn this letter to the editor into a conversation. I spent a Sunday afternoon drafting the following in longhand, and posted it to Gerhard's address.18 June 2017Dr. Falk,I read your letter to the editor in the Buffalo News last week, and I knew immediately that I had to thank you for writing it. Most of the "opinion writing" I encounter is through Facebook, where opiners dash off their thoughts and others dash off their equally hasty replies, few of us really reading let alone thinking about what anyone else has written. I say "written," but this is not writing in the sense I'd like to give to the word. To sit down and write a letter to the editor does require some thought, a careful choosing of one's words - and the barrier to replying is important, too. It is a low and democratic barrier. The only tokens required for crossing are, again, time and thought.I disagree entirely with what you've written, as I will explain further on, but reading your letter was as heartening as a firm handshake. It's taken me some time and thought to discover why.You were correct about something you did not state outright in your letter. We must periodically - and unsparingly - reevaluate the "classics." Popular and critical opinion are often wrong, and many "great" books do not deserve the attention our teachers and peers expect or pressure us to give them. There will be future Gerhard Falks, I hope, to skewer or nudge many recent works wrongly labeled "contemporary classics." Conversely, bold advocates have helped recently to bring new attention to the novels of John Williams - I believe these are classics, and I hope we soon give similar regard to the criticism of M.M. Bakhtin, among others. Then, as you do point out in your letter, we must be aware of and grapple with earlier readers' - and writers' - prejudices. If critics, educators, and students had not pushed for more writers from minority or marginalized groups to appear on college and high school syllabi, generations of school children would have entered adulthood intellectually and aesthetically impoverished, without knowing Zora Neale Hurston, for example.But you are wrong about Shakespeare. Your first mistake is to confuse a reader's endorsement of a writer's works with that writer's endorsement of a reader's actions. I'd venture that many bad and even evil people have enjoyed a line or two from Shakespeare (it's hard for anyone not to - as I'll touch on later). But the fact that The Merchant of Venice was Adolf Hitler's favorite play is irrelevant - not only to the book's literary and aesthetic value, but also to its moral content. Hitler famously liked the operas of Richard Wagner, too - but that doesn't make the Ring cycle or Tristan und Isolde "bad" or "anti-democratic." Perhaps a more pointed example: in your letter you mention the terrorist "bombing" in London. I believe you mean the bombing in Manchester and the bus attack in London. Salman Abedi - the Manchester bomber - and the perpetrators of the London bridge attack all had ties to the so-called Islamic State, and cited lines and rhetoric from the Quran to justify their atrocities. This, of course, does not make the Quran a "bad" book. (Mark David Chapman linked his killing of John Lennon to J.D. Salinger's Catcher in the Rye -- and there are many other examples like this. Were I to mention them all, I'd have to defend them all, for it's never without some reason that a person cites a work of art to justify a crime, hate-speech, or some other type of vileness. But as John Butler Yeats wrote to John Quinn, the lawyer who failed to defend the first American serialization of James Joyce's Ulysses, there is probably no great work that would not be harmful to someone.)Your second mistake is to confuse a character's words and actions with his or her author's beliefs. Yes, in The Merchant of Venice Bassanio, Antonio, and others utter bigotted remarks maligning the Jewish people and perpetuating stereotypes about them. But that does not mean that Shakespeare uncritically held the same beliefs - and it certainly does not mean that The Merchant of Venice encourages or perpetuates racism, "bigotry," or "religious hatred" (to borrow your terms) in any meaningful sense of those words. I'll further venture that your discomfort with some of what the characters say is evidence of the book's power for (moral) good, whether or not one believes that moral content is relevant to its value as art. Many high schoolers who encounter The Merchant of Venice have not (consciously) experienced anti-Semitism, or think of it in ways depersonalized, humorous, and (most dangerously) absurd. (Think, for example, of the anti-Semitism in Sacha Baron-Cohen's movie Borat.) When these students read or see The Merchant of Venice, they find overt anti-Semitism, perhaps for the first time in their lives. Humor here sharpens rather than softens their discomfort. Guided by a teacher who understands the play and its historical context, they can have a meaningful discussion of bigotry and religious hatred as manifested in the book, and then as manifested in their own life experienced. They will leave - hopefully - more sensitive to that bigotry, readier to recognize it when they encounter it in their lives - or in their own thoughts and words.I'll point out here that your claim that Shakespeare's "16th century works are so remote from our present day interests" is not only prima facie ludicrous - the premise of your argument actually defeats it. Shakespeare's works are alive with precisely the biases, hates, passions, and conflicts that continue to infect our world today. The difference is that those biases, conflicts, etc., are subtler, and often encoded. Any work that confronts us with them head-on is relevant, and has some (social, civic) value for that reason.For a further discussion of this topic, see below. NPR's Tom Ashbrook discusses New York City's Shakespeare in the Park production of Julius Caesar - in which Caesar is an obvious Trump.https://www.npr.org/player/embed/532957506/532957516But to return to MoV - I think a closer reading would help. There are other voices besides those of Antonio and Bassanio. Portia, I'd argue, is the most important character, and if anyone "speaks for" Shakespeare, it is her. Like an "author" her intelligence dances over and through every line of the play - and like an "author" she is responsible for resolving the plot.It's worth noting that from early on she exhibits a vexing mix of prejudice and open-mindedness, going sometimes with and sometimes against the grain of her age. You'll remember that one of her suitors, "Morocco," is African, dark-skinned, and expects her to be subject to the aesthetic (really bodily) bias - based on fear and revulsion of the "Other" - dominant in her time and place. Shakespeare chooses to emphasize Morocco's alterity - he is a "tawny Moor" dressed "all in white," to draw out his complexion by juxtaposition. His first line presupposes his desired bride's racism: "Mislike me not for my complexion." He goes on to make an appeal to the equality of human blood (which echoes in later, much more famous lines). Portia's response to this minor character is important: after explaining the rules of her father's will, which govern her fate (and her body), she says that, regardless, "Yourself, renowned prince, then stood as fair / As any comer I have looked on yet ..."She may mean what she says - but it is likely the careful courtesy of a woman alone in a male-dominated world, a woman beset by powerful and potentially violent admirers - a woman whose father has the power to bind, but not to protect her. Because of course, she has earlier compared Morocco to "the devil," and she says something else troubling after. Morocco gives his long-winded and egotistical speech - in which, importantly, he says that he "deserves" Portia (and we are to take this bodily and totally) and spends several lines describing her in terms that objectify her and cast her as an object for the male gaze (cast her, ultimately, in gold) - and in this he is like the white suitor Arragon. Morocco chooses the wrong box. Portia says, "A gentle riddance! Draw the curtains, go. / let all of his complexion choose me so."Has Portia here let slip an admission of literally skin-deep racial bias? This would be out of character in a woman so wise, discerning, and self-aware - but not, of course, unbelievable. Or - casting her relief in relation to the idea of her immanent possession - is she referring to his temperament? The word, in the 16th century, carried both meanings much more so than it does today. It's likely that both are active in this line. Portia objects to his possessive and grandiose attitude as well as to his skin, his visible otherness. But remember again that Shakespeare has not spoken her lines: he has written them, and placed them in a context.Context, here, complicates the meaning of Portia's two racist slights. She first compares Morocco - because of his complexion, which she had not seen - to the devil. Here we realize that Shylock's plight and identity are enfolded "ply on ply" (to borrow from Ezra Pound, another brilliant anti-Semite, whose work transcends his "parochial" biases, as he later described them in a lament to his friend Allen Ginsberg) with the identity and plight of Morocco. Shylock, too, is compared to the devil.Shakespeare places both on the same side of the simplistic light/dark, good/bad dichotomy by which his characters classify everything in their world. This becomes obvious when in a later scene Salarino mocks Shylock, who is bemoaning his lost daughter, by saying "There is more difference between thy flesh and hers than between jet and ivory ..."It is clear that in these lines and in the structure of the play Shakespeare links the Jew and the Moor, and thereby draws our attention to this link. So let us return to Morocco. The African prince's downfall is that he has developed a reverence for appearances. (Here, again, a 16th century concern is immediately relevant to our present-day culture. African American literature, hip-hop lyrics, and criticism are full of rich discussions of how materialism and an obsession with appearances are byproducts of poverty marginalization, and living in a culture that shames one's body. Remember that Morocco dresses in white. He insists that he deserves Portia -- but not because of his equal humanity. He deserves her because he is rich and powerful. He is demanding a specious but all-too familiar sort of equality; he is trying to "pass."We may safely say that Portia is repulsed by the appearance of a man obsessed with appearance. The deeper irony come when he chooses the wrong box, which contains a message telling him that "All that glisters is not gold," and "Gilded tombs do worms enfold." These, too, are as much Shakespeare's words as were the references to the visible otherness and "devil." And they are as relevant to Morocco as they are t Portia, Bassanio, Salario, and all the others. With a childishly simple admonishment not to judge by appearances, on Morocco and Portia both hear, Shakespeare subtly challenges the prejudicial culture - the culture that associates white with good and dark with evil - in which his characters live - and in which he lived, too.Any attuned ear will hear the words locked in the gold chest echoed in that later scene, when Shakespeare gives Shylock, the Jew (whose culture and environment, it is clear, made him hateful and bloodthirsty) the most powerful lines in the play.Shylock challenges the scorn and prejudice Bassanio and his like heap upon him -- but more importantly he challenges these as "givens," things that the culture assumes.

I'll further venture that your discomfort with some of what the characters say is evidence of the book's power for (moral) good, whether or not one believes that moral content is relevant to its value as art. Many high schoolers who encounter The Merchant of Venice have not (consciously) experienced anti-Semitism, or think of it in ways depersonalized, humorous, and (most dangerously) absurd. (Think, for example, of the anti-Semitism in Sacha Baron-Cohen's movie Borat.) When these students read or see The Merchant of Venice, they find overt anti-Semitism, perhaps for the first time in their lives. Humor here sharpens rather than softens their discomfort. Guided by a teacher who understands the play and its historical context, they can have a meaningful discussion of bigotry and religious hatred as manifested in the book, and then as manifested in their own life experienced. They will leave - hopefully - more sensitive to that bigotry, readier to recognize it when they encounter it in their lives - or in their own thoughts and words.I'll point out here that your claim that Shakespeare's "16th century works are so remote from our present day interests" is not only prima facie ludicrous - the premise of your argument actually defeats it. Shakespeare's works are alive with precisely the biases, hates, passions, and conflicts that continue to infect our world today. The difference is that those biases, conflicts, etc., are subtler, and often encoded. Any work that confronts us with them head-on is relevant, and has some (social, civic) value for that reason.For a further discussion of this topic, see below. NPR's Tom Ashbrook discusses New York City's Shakespeare in the Park production of Julius Caesar - in which Caesar is an obvious Trump.https://www.npr.org/player/embed/532957506/532957516But to return to MoV - I think a closer reading would help. There are other voices besides those of Antonio and Bassanio. Portia, I'd argue, is the most important character, and if anyone "speaks for" Shakespeare, it is her. Like an "author" her intelligence dances over and through every line of the play - and like an "author" she is responsible for resolving the plot.It's worth noting that from early on she exhibits a vexing mix of prejudice and open-mindedness, going sometimes with and sometimes against the grain of her age. You'll remember that one of her suitors, "Morocco," is African, dark-skinned, and expects her to be subject to the aesthetic (really bodily) bias - based on fear and revulsion of the "Other" - dominant in her time and place. Shakespeare chooses to emphasize Morocco's alterity - he is a "tawny Moor" dressed "all in white," to draw out his complexion by juxtaposition. His first line presupposes his desired bride's racism: "Mislike me not for my complexion." He goes on to make an appeal to the equality of human blood (which echoes in later, much more famous lines). Portia's response to this minor character is important: after explaining the rules of her father's will, which govern her fate (and her body), she says that, regardless, "Yourself, renowned prince, then stood as fair / As any comer I have looked on yet ..."She may mean what she says - but it is likely the careful courtesy of a woman alone in a male-dominated world, a woman beset by powerful and potentially violent admirers - a woman whose father has the power to bind, but not to protect her. Because of course, she has earlier compared Morocco to "the devil," and she says something else troubling after. Morocco gives his long-winded and egotistical speech - in which, importantly, he says that he "deserves" Portia (and we are to take this bodily and totally) and spends several lines describing her in terms that objectify her and cast her as an object for the male gaze (cast her, ultimately, in gold) - and in this he is like the white suitor Arragon. Morocco chooses the wrong box. Portia says, "A gentle riddance! Draw the curtains, go. / let all of his complexion choose me so."Has Portia here let slip an admission of literally skin-deep racial bias? This would be out of character in a woman so wise, discerning, and self-aware - but not, of course, unbelievable. Or - casting her relief in relation to the idea of her immanent possession - is she referring to his temperament? The word, in the 16th century, carried both meanings much more so than it does today. It's likely that both are active in this line. Portia objects to his possessive and grandiose attitude as well as to his skin, his visible otherness. But remember again that Shakespeare has not spoken her lines: he has written them, and placed them in a context.Context, here, complicates the meaning of Portia's two racist slights. She first compares Morocco - because of his complexion, which she had not seen - to the devil. Here we realize that Shylock's plight and identity are enfolded "ply on ply" (to borrow from Ezra Pound, another brilliant anti-Semite, whose work transcends his "parochial" biases, as he later described them in a lament to his friend Allen Ginsberg) with the identity and plight of Morocco. Shylock, too, is compared to the devil.Shakespeare places both on the same side of the simplistic light/dark, good/bad dichotomy by which his characters classify everything in their world. This becomes obvious when in a later scene Salarino mocks Shylock, who is bemoaning his lost daughter, by saying "There is more difference between thy flesh and hers than between jet and ivory ..."It is clear that in these lines and in the structure of the play Shakespeare links the Jew and the Moor, and thereby draws our attention to this link. So let us return to Morocco. The African prince's downfall is that he has developed a reverence for appearances. (Here, again, a 16th century concern is immediately relevant to our present-day culture. African American literature, hip-hop lyrics, and criticism are full of rich discussions of how materialism and an obsession with appearances are byproducts of poverty marginalization, and living in a culture that shames one's body. Remember that Morocco dresses in white. He insists that he deserves Portia -- but not because of his equal humanity. He deserves her because he is rich and powerful. He is demanding a specious but all-too familiar sort of equality; he is trying to "pass."We may safely say that Portia is repulsed by the appearance of a man obsessed with appearance. The deeper irony come when he chooses the wrong box, which contains a message telling him that "All that glisters is not gold," and "Gilded tombs do worms enfold." These, too, are as much Shakespeare's words as were the references to the visible otherness and "devil." And they are as relevant to Morocco as they are t Portia, Bassanio, Salario, and all the others. With a childishly simple admonishment not to judge by appearances, on Morocco and Portia both hear, Shakespeare subtly challenges the prejudicial culture - the culture that associates white with good and dark with evil - in which his characters live - and in which he lived, too.Any attuned ear will hear the words locked in the gold chest echoed in that later scene, when Shakespeare gives Shylock, the Jew (whose culture and environment, it is clear, made him hateful and bloodthirsty) the most powerful lines in the play.Shylock challenges the scorn and prejudice Bassanio and his like heap upon him -- but more importantly he challenges these as "givens," things that the culture assumes.

--and what's his reason? I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

In all of literature I do not know of any more affecting lines appealing to a common humanity, piercing all real and perceived difference, and sweeping over the centuries -- from Shakespeare's day to ours, and, I'm sure, far beyond.Acknowledge, please, the beauty of these words. Acknowledge their terrible hard directness, the pain behind the appeal, the way it soars to the noblest sentiments before plunging to the evilest -- and both noble and evil pure, purely and uniquely human passions. It is so true -- so terribly true, so timeless. so moving and so beautiful.The words are more moving and beautiful than Portia's later memorable appeal for mercy. You accuse Shakespeare of "hate-mongering." Pandering to low biases, certainly -- but mongering hate? This same Shakespeare put the foregoing appeal for quality and shared humanity in his "villain's" mouth. Shylock is no puppet of prejudice, no stereotype. No -- instead of hate-mongering, Shakespeare confront his audience -- minds comfortable in bias and used to dealing in stereotypes -- with a Jewish character at once a "villain" and immensely empathetic, a character so real he reaches up out of the pages to point and demand our guilty hearts. And that same "hate-mongering" Shakespeare has his Portia say hat mercy "droppeth gentle as the rain from heaven ... It is twice blest: / It blesses him that gives and him that takes ... It becomes the throned monach better than his crown ... It is an attribute to God Himself; / And earthly power doth then show likest God's when mercy seasons justice." Context, again, is crucial: Shylock does not choose mercy, but Shakespeare will not let us blame him -- for we feel ourselves with him rejecting Portia's (empty, empty) words.And make no mistake: Some in Shakespeare's audience would have cheered at Shylock's conversion, and even Shakespeare himself might have imagined some "justice" in that neat conclusion, but across the centuries it carries the full force of Greek tragedy: warped by his encagement and abuse, brought down by fidelity to his lowest passions, trapped by the law in which he put all of his faith, the law where he thought he might be equal to a Christian, Shylock is Shakespeare's most lifelike and powerfully drawn tragic figures. We cannot "judge" tragic figures the way we judge true heroes and true villains, for, as Aristotle said in his Poetics, their tragic status and their forces comes from our identification with them.Authors do not share their characters' every belief and prejudice, and they do necessarily not share their characters' virtues -- but Shakespeare authored these appeals to understanding an to mercy, and nothing in the play undercuts these as values (though arguably none of the characters live up to them). You would prefer authors more supportive of our democratic values." But do you know of any author who has written more forceful appeals to our democratic values of egalitarianism, equality before the law, freedom of belief, and mercy?You would be hard-pressed to find one. Certainly I cannot think of any great number of authors jostling to replace Shakespeare on our bookshelves and in our curricula by this standard alone.But this standard you choose is troubling. "Support of our democratic values" is a dangerous measure by which to judge literature's merits. It presupposes the immutable righteousness of these values -- when we know that the values themselves may seem to narrow in a later age, and that the individuals who wield the power to interpret them may be wrong, and may even intentionally corrupt them. Where art must serve the state, art inevitably atrophies and suffocates; propagandists survive while true artists are jailed or even killed, and the citizens of such a state are deprived of their works. Such was the case in Russian under Stalin and is the case under Putin today. America has sometimes exhibited a similar tendency to restrain art -- or, even more insidiously, to promote non-art. And remember that it was the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels (who could, I think, have had a remarkable career as a culture critic had he not bent his immense cultural intelligence to the purest manifestation of evil) who said that "There must be no art in the absolute sense, such as a liberal democracy acknowledges ... [which] would end in the people's losing all internal contact therewith and the artist's becoming isolated in a vacuum of art for art's sake." Goebbels' understood the power of "art" warped to serve a state's will -- and the power of a free art, like Shakespeare's.Like Plato, you undervalue beauty and overvalue stability. Shakespeare's works are beautiful, and this is not a matter for the eye or the ear of the proverbial beholder to decide. The lines sing and enchant -- the action proceeds, complicates, and resolves itself symphonically -- in every syllable and motion you can hear the "click of a well-made box." If you do not recognize this beauty or feel it as valuable for its own sake, then there is nothing I can say or do for you other than invite you to Stratford, Ontario where we might watch some very fine Shakespeare together. Even sooner we might go to Shakespeare in Delaware Park, which is often fine.

. . .

But your chief concern is moral good and value to our civic culture -- so be it -- having registered my warnings about such a worldview, I will champion Shakespeare there, too.Perhaps Shakespeare shared the common prejudices of his day. Or perhaps he was "enlightened" and possessed only prejudices similar to those that reign in our day (like belief in the inherent inferiority of women, the separation and inequality of he "races," anti-Semitism, or any form of revulsion at an unfamiliar "Other"). As lines here and there suggest, its probable that Shakespeare suffered from a lack of exposure to people and cultures different from himself and from his, harbored some suspicions and biases, or, at the very least, pandered to the same in his audience.But as is obvious from the lines I quote above and from all his plays generally, despite whatever shortcomings we impute to him, Shakespeare was an artist preternaturally sensitive to bias, hypocrisy, and all the base, vile, and "fallen" parts of human nature. Can we ask any more of an artist than that he bear witness to his own weaknesses and explore them critically and unsparingly? Shakespeare does explore them, using irony, counterpoint, juxtaposition, symbolism, monologue, and dialogue -- and we explore it with him. Whether we encounter The Merchant of Venice alone or with a group, Shakespeare provokes us into crucially uncomfortable reflection on bias, racism, anti-Semitism, and the ways in which these things are encoded in our customs and language; as well as gender politics, male control of female fates and bodies, the objectification of women, and imprisonment of marginalized groups (among which we number Portia, Morocco, Jessica, and Shylock, each imprisoned in cages that the dominant class constructed -- laws, wills, boxes, customs, clothes, and more).Above all this it explores love, revenge, power, mercy, and the role of one's environment in suppressing or feeding all of these human impulses. Shakespeare does this in The Merchant of Venice and in all of his plays, which provoke us through encounters with madness (King Lear); ambition, power, and corruption (Macbeth); and (sexual) love for an "Other" and the purest evil engendered too often in our reaction to it (Othello).All of these discussions are immediately relevant to our culture, and that is why we still read and produce Shakespeare -- for that burning relevance, and for his burning, peerless beauty. Beauty and ugliness, good and evil, bias and noble feeling, mercy and revenge, are all mixed in his works, and the result is truth: truth that shakes us, offends us, delights and entrances us, enlivens us to every impression, good and bad; it silences us and moves us to speak; it saddens us; it reacquaints us with our fellow humans. I cannot say that great art makes us better humans -- and the vileness that must o into any work true and capacious enough to become a "classic" may even do harm to some susceptible mind, as John Butler Yeats said -- but Shakespeare does all that I have said above, and for those reasons we must continue to read, speak, and hear his words, the beautiful as well as the troubling, and open ourselves up to the effects they might have on us.Then, of course, we have to talk about it.Yours,Aidan Ryan